The war in Afghanistan is the problem that never seems to go away. Every U.S. president since George W. Bush has tried to find the magic formula to Afghanistan’s success. And every president has come up empty handed. They failed because Afghanistan is, indeed, an unsolvable problem.

Former Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump could not have been any more different in terms of ideology and personality, but the two had a common experience very early on in their tenures.

Obama came into office with the war in Afghanistan at a low point. The Taliban insurgency at the time was chipping away at the Afghan government’s territorial control. The U.S. war strategy was geared toward sustaining a stalemate on the ground.

After a nearly year-long inter-agency policy review, Obama—surrounded by heavy hitters like Defense Secretary Bob Gates, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Mike Mullen and commander Stanley McChrystal—was reluctantly convinced (some would say, pressured) to deploy an additional 30,000 American soldiers to clean up a conflict that was going badly, quickly. Hundreds of U.S. casualties and hundreds of billions of dollars later, the end result was depressing but familiar: more stalemate.

Trump, too, couldn’t resist the recommendations of his more hawkish national security advisers. The 45th president of the United States came into the White House highly skeptical there was anything Washington could do to make Afghanistan a more stable place.

He had long bemoaned the U.S. war effort there as a waste of lives and taxpayer dollars, a failed investment full of sunk costs and shoddy returns. Yet despite his instincts to pull out, Trump agreed to a try a mini surge off his own, dispatching close to 4,000 additional troops and increasing the use of airpower against the Taliban. The objective: To level the playing field and pound the Taliban into a peace negotiation with the Afghan government. The verdict: The beginning of a low, slow and moribund intra-Afghan peace process coexisting alongside the same old war that has been proceeding on an endless loop since early in the century.

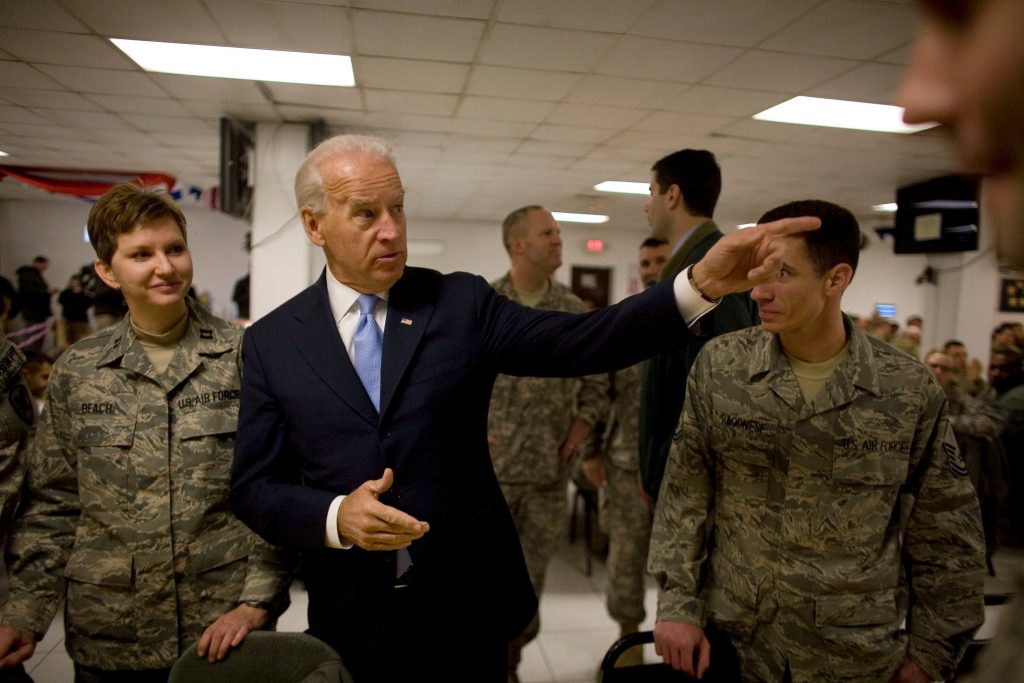

Now it’s President Biden’s turn. Like his immediate predecessor, Biden has never been enthralled with the notion of nation-building in Afghanistan.

During his earlier stint as vice president in the Obama administration, he was the principle bulwark against the Pentagon’s counterinsurgency strategy in the South Asian country. Biden’s doubts about what the U.S. can and cannot accomplish have not softened with age.

When asked by Margaret Brennan of CBS News a year ago whether he would hold some responsibility in the event the Taliban returned to power after a U.S. troop withdrawal, Biden was emphatic.

“Zero responsibility,” Biden answered. “The responsibility I have is to protect America’s national self-interest and not put our women and men in harm’s way to try to solve every single problem in the world by use of force. That’s my responsibility as president. And that’s what I’ll do as president.”

It was a clear, passionate and level-headed response by the then-presidential candidate. Underlying Biden’s answer was critical recognition that as powerful, wealthy and capable as the United States is, there are some issues Washington can’t resolve. Whether Biden will continue to be as clear-eyed on this never-ending war now as he was then being still to be determined.

There are those in Washington who hope Biden will do what Obama and Trump did before him: defer to the national security “experts” and keep the U.S. military stationed in Afghanistan until the miracle of peace blossoms across the land.

Many of these people are former senior military officers who at one point in their careers commanded or at least had some responsibility for the war effort. One of the most recent efforts was led by Retired Gen. Joe Dunford, the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who co-chaired the congressionally-mandated Afghanistan Study Group.

The core recommendation from the glossy 84-page report released last week: delay the May 1 U.S. troop withdrawal until the Taliban meets a series of strict conditions, such as reducing violence against the Afghan government. If convincing the Taliban to abide by its commitments isn’t possible, keep U.S. troops on the ground and continue to support Kabul militarily, diplomatically and economically “for the foreseeable future.”

The Biden administration has since said it would take the Afghanistan Study Group’s report under advisement as it conducts its own policy review. The administration, however, would be better off ignoring its central conclusion, which practically allows the Taliban and the Afghan government veto power over when U.S. troops can come back to their families.

If the president is genuinely committed to closing the book on a two decade-long misadventure in Afghanistan—one whose narrow counterterrorism mission against Al-Qaeda quickly snowballed into an expensive and dangerous permanent babysitting gig on behalf of the Afghan political elite—he needs to resist the temptation of accepting the same, old advice.

One of the biggest myths that continues to hover over the U.S. foreign policy establishment like a dense fog is the notion that the U.S. will not be safe from transnational terrorism until Afghanistan is stabilized.

It’s a myth that presumes the U.S. military needs a ground presence to protect itself and one that totally discounts the capacity of the U.S. counterterrorism apparatus to monitor and neutralize terrorist threats quickly and decisively.

Joe Biden is now presented with an opportunity to puncture this myth. The only alternative is adding even more years on top of America’s longest war.