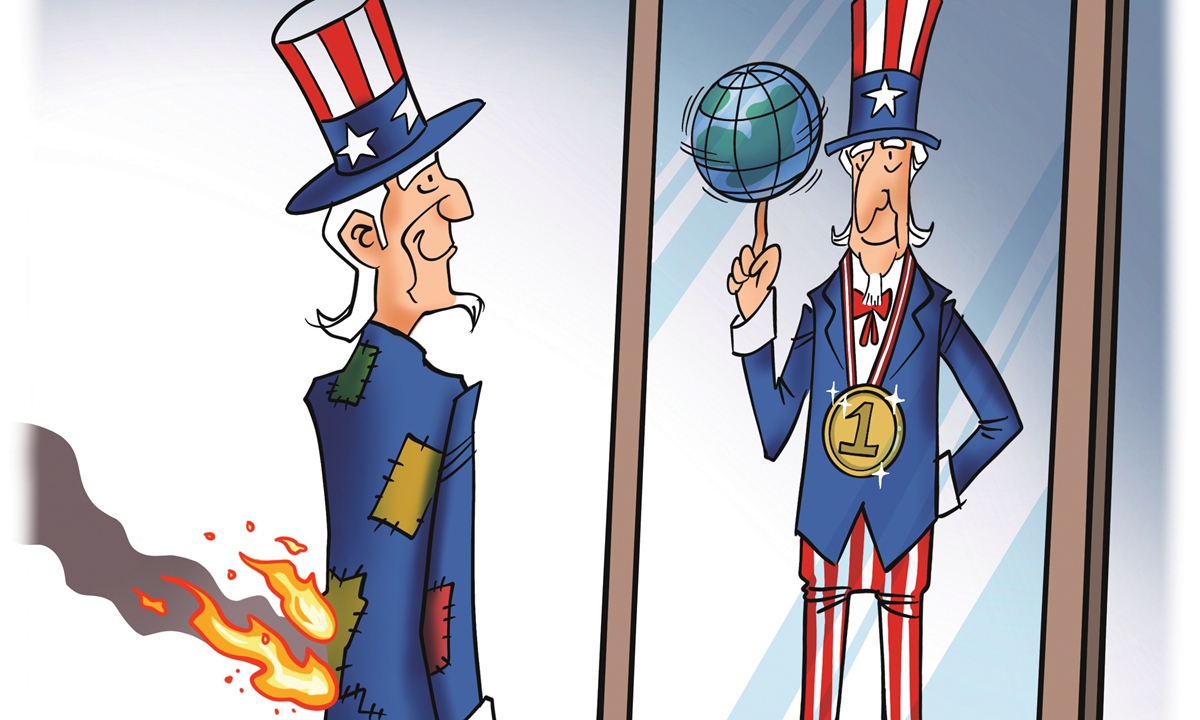

While the US has come to realize that it is not as omniscient and omnipotent in East Asia as it once was after World War II, the country continues to act as if it is. Its strategy is contracting, as the US is trying to shift its strategic focus from Europe and the Middle East to the Indo-Pacific region to deal with China specifically.

For US allies, the appeal of the US to a certain degree lies in the potential for access to the US market and attracting US investments. However, Joe Biden’s “middle-class diplomacy” means that the US remains focusing on domestic issues, making it less likely to open its market to allies as it did in the past. The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) for Prosperity proposed by Biden is not about opening up the US market, so it does not have practical appeal to East Asian countries. Moreover, Donald Trump, who is running for US president again, has already declared that he will kill off the IPEF once he takes office. In order to deal with the China-proposed Belt and Road Initiative, the US has made huge infrastructure investment commitments to different regions and countries in recent years. However, it lacks the capacity to turn promise into reality.

This is also the case with the Taiwan question. Although various pro-Taiwan political forces in the US have been calling on their country to adopt a policy of strategic clarity regarding the Taiwan question instead of the current strategic ambiguity, US authorities can hardly make such a strategic shift.

Whether it is the countries involved in the South China Sea issue, such as the Philippines, or the Taiwan region, none of them can be sure whether the US will provide defense in the event of a conflict with the Chinese mainland. The US’ strategic ambiguity on its promise proves that it admits it is no longer omniscient or omnipotent.

As mentioned earlier, US interests are deeply embedded in various regions, making it difficult for the US to leave other regions behind and focus solely on the Indo-Pacific region to counter China. These embedded interests indicate that the US lacks sufficient resources to intervene in potential conflicts in region on a larger scale. Although the US’ defense spending and naval power still rank first in the world, it has fewer ships than China in West Pacific. Once in a state of war, the US Navy can hardly withdraw without incurring a high cost. In fact, many analysts believe that if the US and China were to fall into direct conflict, it would accelerate the decline of the US’ global power, regardless of the outcome.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict and the Israel-Palestine conflict are just two examples clearly showing that the US is not providing defense to the countries it claims to protect with its own military power, but rather with military aid and technology transfer. In other words, the US is actually turning these countries into its proxies. In fact, whether it is Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, or the Taiwan region, there are people who realize that the so-called defense commitment from the US is more of a strategic ambiguity, lacking any certainty.

Today’s East Asia presents an interesting situation. In order to maintain its reputation and interests, the US continues to pretend to be “omniscient and omnipotent.” However, it realizes that it is not, and therefore it is turning to cognitive warfare to portray China as an “enemy” and emphasize its allies’ dependence on the US. Allies of the US pretend to believe that the US is still omniscient and omnipotent. They lean heavily toward the US and deepen their relationship, trying to gain even the smallest benefits from it.

For those who enjoy Hollywood blockbusters, it is very common to hear lines from the main characters complaining how their God no longer exists and now they have to rely on themselves. In fact, countries like Japan and the Philippines also face a similar situation. They treat US power as a belief. But to what extent can the US actually help them? Perhaps only God knows.

The author is a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen and president of The Institute for International Affairs, Qianhai. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn