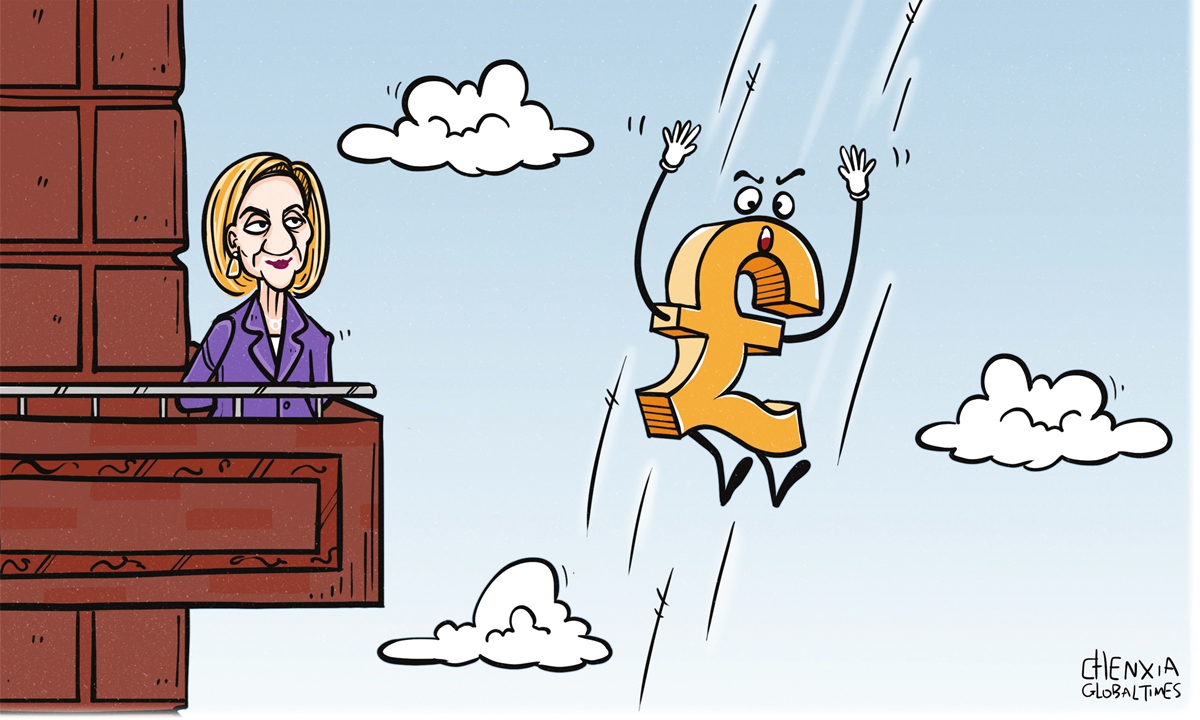

The difference between the optimism of Britain’s new prime minister, Liz Truss, and the state of the British economy, could not be more different. Just last week on her official social media account, she posted: “Our Growth Plan will unleash our potential and deliver better jobs, more funding for public services and higher wages for the British people.”

But the UK prime minister lives on a different planet. As she puffs up prospects of growth and potential, the British pound as of Monday morning has continued crashing down to a 37-year low, which has brought it on near parity with the US dollar, at just $1.03. Just over five years ago, it stood at over $1.50.

But while currencies all over the world are reacting to US aggressively ratcheting up interest rates, that isn’t the only problem Britain faces. A lot of it is self-inflicted. Inflation is also at eye-wateringly high levels, and is expected by economists to potentially even reach 22.4 percent by next year. Real wages are down, and the Bank of England has already declared that the UK is in a technical recession already.

But if you believed Britain’s leaders, you would never assume any of this is true. You would think the country is entering a glorious new era in the name of “Global Britain.” But this is in fact the problem. Although some factors cannot be controlled, the miserable economic performance of the UK is a product of the country’s increasingly and overtly ideological foreign policy which, while starting with Boris Johnson, is only set to get worse under Truss.

In 2016, Brexit marked a fundamental turning point in British foreign policy, in that ideology and identity prevailed over reason and pragmatism. The United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union was not premised on economic reason or logic so to speak, but the same national identity-driven backlash against globalization which has increasingly taken hold across the West, ironically itself a consequence of decades’ worth of liberal capitalism. In doing so, “Brexit” led to a new foreign policy discourse increasingly shaped by British exceptionalism floated on a nostalgia of empire and global dominance.

While in the initial months of the Johnson premiership such a narrative depicted China as an opportunity, as the US manipulated discourse concerning the country and twisted public opinion against it, putting pressure on the UK to follow its foreign policy line, “Global Britain” was soon seized by neoconservatives such as Truss who further morphed it into the lexicon of geopolitical power struggle and global ideological conflict, which further reflects the theme of diminished Western hegemony in the view of rising powers. In effect, Brexit was no longer about looking back to the past, but attempting to revisualize the glory of a British-dominated world by militarism and economic policies premised purely on ideology, hence the UK has taken an aggressive collision course against both China and Russia.

Being completely ideological of course, such a policy is in fact disastrous for British interests in practice. Truss has signaled she is only willing to initiate closer trading ties with other democracies, rather than on actual economic realities, and despite the fact that Brexit has alienated the UK as it is from one of its largest and closest markets, the EU. Likewise, the US, owing to its new consensus of “America First” protectionism, has made it clear multiple times that it is not interested in a trade agreement with Britain, which has been an obsessive ideological product of Brexit.

Despite all of this, Truss now speaks about “reducing strategic dependence on China” – another critically important export market for the UK. This comes in the middle of a mounting economic crisis, with the early decisions to lower taxes having decimated the value of the pound. Economists have warned that with rising national debt simultaneously (being the highest since World War II), the UK is on the brink of a potential economic disaster and that the current trajectory is not sustainable. But this does not seem to phase the government, which has long stopped caring about facts in favour of ideology.

Given this, a potential distancing from China in the middle of such grim prospects could be catastrophic for Britain, especially when existing inflation is taken into account, costs of living are rising and supply chains are already strained in the midst of Brexit. In respect to both Russia and China, Truss must pull back from the brink and recognize that the UK’s increasingly aggressive and irrational foreign policy is only hastening its long-term decline, much to the benefit of the US, as opposed to bringing about a renaissance. Will the UK come to its senses? Will ordinary people speak up as standards of living continue to be squeezed? Don’t count on it.

The author is a political and historical relations analyst. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn