To do so, let us use an important methodological principle. The realms of thought, culture, philosophy, and politics, are part of what we may call the “superstructure.” However, one cannot have a superstructure without a foundation. The foundation is economic.

In light of this distinction we may ask: in terms of the economic base, what are the objective conditions that may lead to a conflict? There are two primary conditions: economic depression and geopolitical changes. As for the geopolitical situation, despite provocations by the US concerning the Taiwan question and despite Japanese provocations concerning some islands, there have been no significant geopolitical changes.

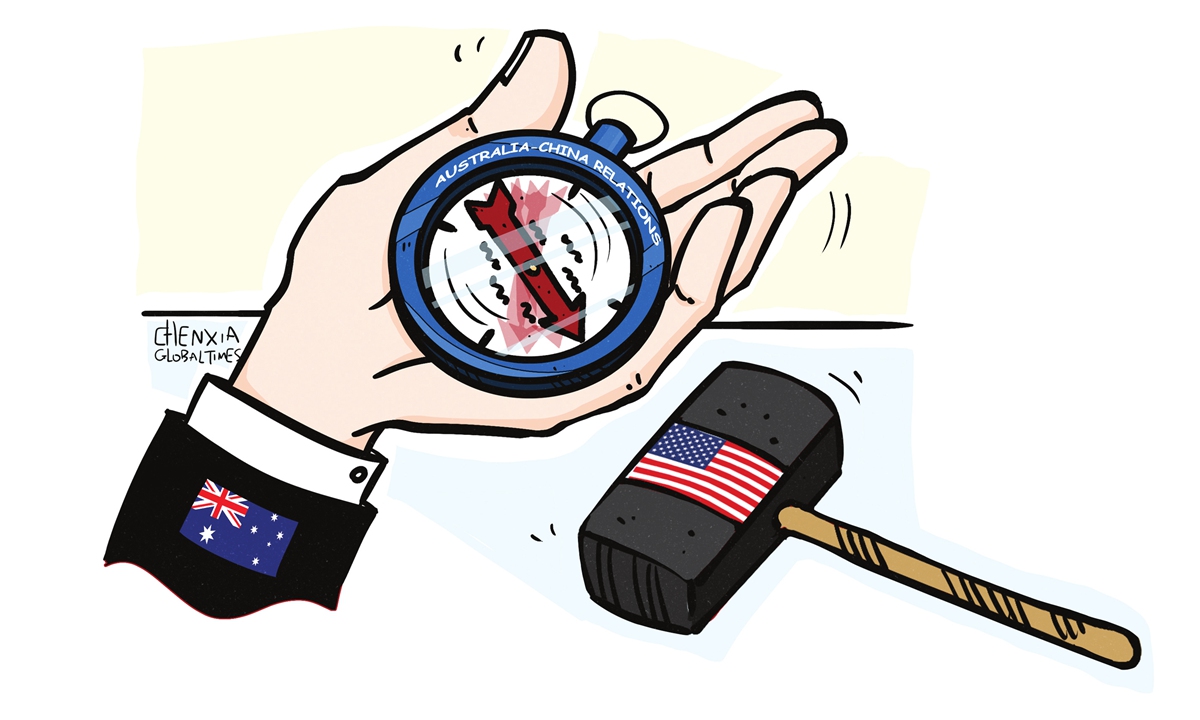

I would like to say more concerning economic realities, specifically with regard to China-Australia relations. For many years now, China has been Australia’s No.1 trading partner. The two economies are highly complementary, and any Australian business that is serious about its bottom line is seeking to deepen its engagement in China. At the forefront of these activities are organisations such as the Australia-China Business Council and the Australia-China Chamber of Commerce, respectively based in Australia and China. As China has stepped out of the COVID-19 pandemic and sprinted into 2023, these organisations are increasingly busy.

From my own experience of applying for a visa and returning to Beijing, I can attest that I had to wait weeks for an appointment and that the visa office I attended was processing 700-800 applications per day. Even with extra staff, the visa office would often work until after 6pm every evening. Further, the plane on which I flew was full, and one can assume that the many other flights on the China-Australia route are also full.

Clearly, from economic realities to person-to-person exchanges, the situation is improving day by day.

To return to the objective conditions for conflict, it should be clear that in the region of East Asia and Southeast Asia there is neither geopolitical change nor economic depression. These objective conditions mean that war is highly unlikely. To be sure, the US would love to see third parties engage in a useless conflict with one another. However, without the basic conditions, it is unlikely that Australia or any other country in Southeast Asia will engage in conflict soon.

What then are we to make of the talk in Australia of “war with China” and the “China threat.” A rational observer can see that this is empty talk, without foundation in reality. To use my earlier distinction, this talk is very much part of the “superstructure.”

But the talk does have a purpose. If we look back five or so years, we will find that one or two “think tanks” were established with funding from major US and UK weapons manufacturers. These began promoting the fake “China threat” narrative and the “war with China” line. With thousands of variations on the same theme, they gained traction in the Australia media and began to gain some influence. In the end, it was less about influencing the Australian public and more about swaying the politicians in Canberra. These politicians have eventually responded with increases in military spending to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars. For the weapons manufacturers, this result would be seen as a very good “investment.” Hype a fake threat, gain traction with the power-brokers, and the result is a massive amount of taxpayer dollars – taken from health, education, and so on – disappearing into the bottomless pockets of weapons manufacturers.

One may wonder what business leaders seeking to deepen engagements with China think about these developments. Let me put it this way: among the economic and political elite in Australia there is a profound contradiction. One the one hand, we have many businesses deepening their engagements with China and they are certainly against any provocations since these would interfere with their core interest; on the other hand, we have a smaller number aligned with the military and the overseas weapons manufacturers, and they are keen to grab as many taxpayer dollars as possible.

This contradiction is a profound challenge for the current Labor government in Canberra. Currently, the government is swaying this way and that: seeking to improve relations with China and at the same time committing huge amounts of money for military spending. This approach is certainly not a way to manage a significant contradiction. Only the future will tell if they can learn to manage the contradiction in a better way.

The author is a Marxist scholar from Australia, distinguished overseas professor at Renmin University of China, and on editorial board of the Australian Marxist Review. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn