By Ji Yuqiao and Xu Liuliu

As soon as Chinese writer Ma Boyong settled into the interview with the Global Times, he posed a curiosity-sparking question: “Do you know how evaluation systems of the key performance indicator (KPI) were implemented in ancient China?”

Just like his best-selling novels, which have been sold several million copies, the 44-year-old, following the beginning focused on ties between history and reality, began recounting how he stumbled upon ancient bamboo slips during a visit to the Nanyue King Museum in South China’s Guangdong Province. These slips recorded daily quotas for tasks, such as the number of rats each person was required to catch, as well as the penalties for failing to meet the targets.

This is quintessential Ma Boyong – whose writing style and craft revolve around finding inspirations in the seemingly mundane. Through his ability to extract stories from historical fragments, Ma attempts to deliver vivid details from 1,000 years ago into the hands of modern readers.

“It’s actually simple,” he shared. “You just need to find something that excites you. With China’s 5,000-year-old history, it’s not hard to find such sources of inspiration.”

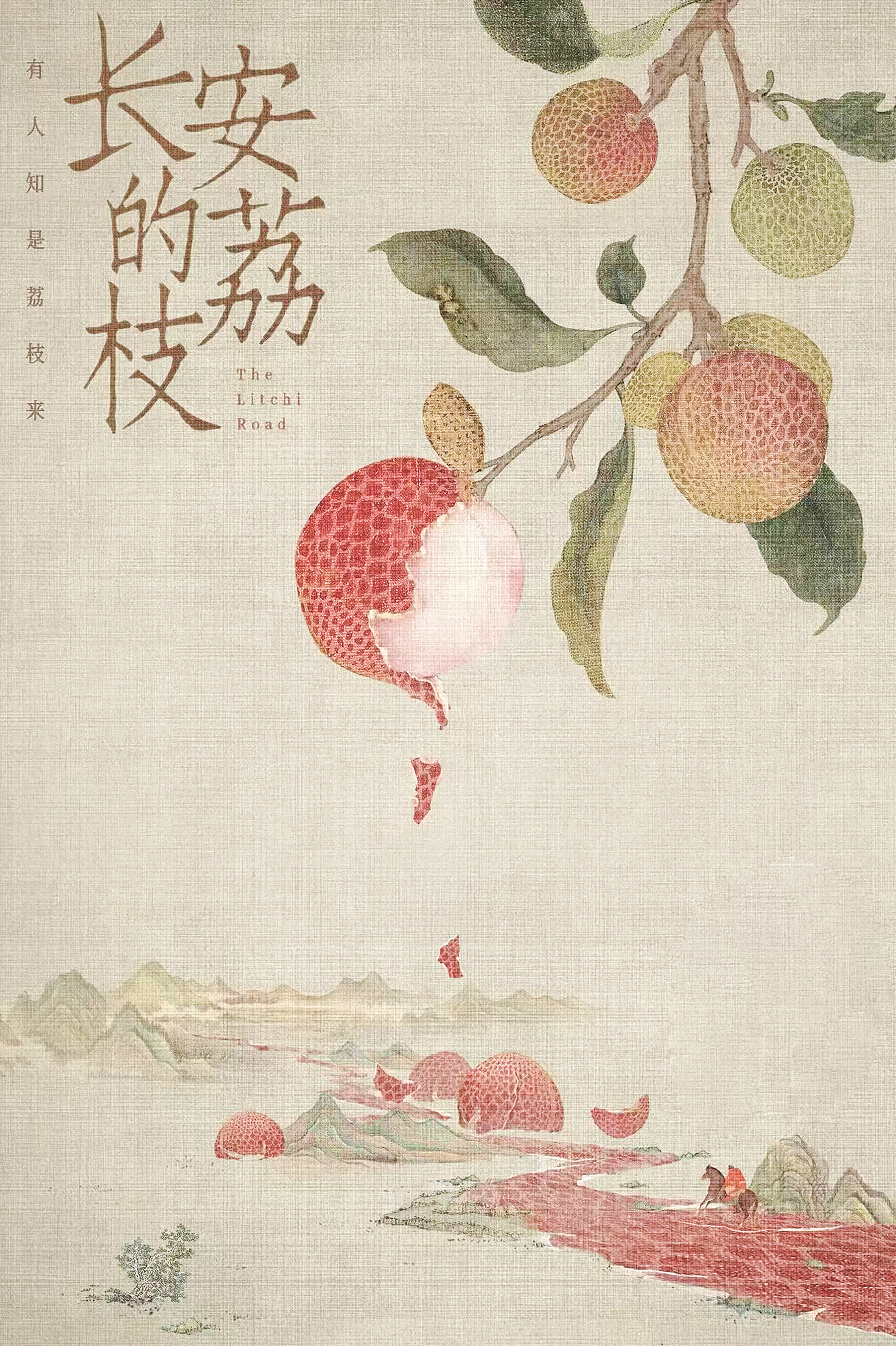

The front cover of the novel The Litchi Road Photo: Courtesy of Maoyan

Balance between dramatization and seriousness

“A steed which raised red dust won the fair mistress’ smiles; no one knows how the lychees have arrived.” This line from an ancient Chinese poem is deeply etched in the collective memory of the Chinese people. But while most readers focus on the “smiling concubine” in the first half of the verse, Ma is fixated on the latter half: How fresh lychees were transported from the southern Lingnan region to Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an, capital of Northwest China’s Shaanxi Province) without spoiling. This curiosity about transportation logistics from the Tang Dynasty (618-907) became the basis of his 70,000-word bestselling novel The Litchi Road.

Discovering dramatic details hidden within the lines of history is only the first step. To balance the seriousness of historical facts with the intrigue of a novel, Ma relies on extensive research, meticulous accumulation of information and further deconstruction of the details.

Ma noted that he has a habit of breaking down a difficult task into a dozen smaller problems, solving them one by one, and then gathering the necessary information. In doing so, he often finds that what initially seemed impossible is actually achievable. When writing The Litchi Road, Ma approached it from the perspective of a project manager, following the process of advancing a project step by step until the story was completed.

For his other book Liang Jing Shi Wu Ri (lit: Fifteen Days Between Two Capitals), Ma admitted that while there are many fictional elements in the work, the historical logic within it is entirely authentic. What kind of horses people rode, the roads they traveled, and even the routes they took along the Grand Canal – these details were all things he had discovered in historical records.

He then built upon them with some interpretation and creative elaboration.

As one reader, who claimed to have been following Ma’s works since 2003, commented on a book review website: “He is an interesting writer whose works brilliantly combine authentic and serious content with a humorous writing style, making [his works] truly shine.”

Bridge across time

Ma adheres to a core principle when writing historical fictions: It must connect with reality. He hopes readers will “close the book, look up, and see the historical site right before their eyes.” Whether it be feeling inspired to visit Xi’an, walk along the Grand Canal, or taste lychees after reading his works, he sees it as a positive process of transitioning from the page to real life.

Ma has always remembered the story of a college student in Xi’an after finishing The Longest Day in Chang’an. Over the period of four years, the reader explored every street and alley of the city, and is now endorsed by Ma as being more knowledgeable than he, and can even point out historical errors in Ma’s works.

“A novel is like a window, through which you catch a glimpse of a broader sky. Then, you can discard the window, step through it, and walk into that wider sky. That is the most beautiful outcome,” Ma said. Seeing young people focus on exploring historical events and places fills him with joy, as he believes this aligns perfectly with one of the fundamental purposes of his writing.

The growing enthusiasm for historical events among the younger generations, which is reflected by the popularity of his works, is a sign of increased cultural subjectivity and confidence, Ma noted.

“Young people have been the main force in a variety of cultural fields. They are making step-by-step contributions in their own unique way,” the writer observed. “When you look at how traditional and popular cultures are blending today compared with 10 or 20 years ago, it is a completely different picture.”

The lychees from the Lingnan region ultimately made their way to Chang’an, and the defense of the ancient capital of the Tang Dynasty continues.

Novelists will eventually step away from their stories and immerse themselves in other literary pursuits. Perhaps the KPI evaluation system of the Nanyue Kingdom more than 2,000 years ago might become the starting point for Ma’s next novel.