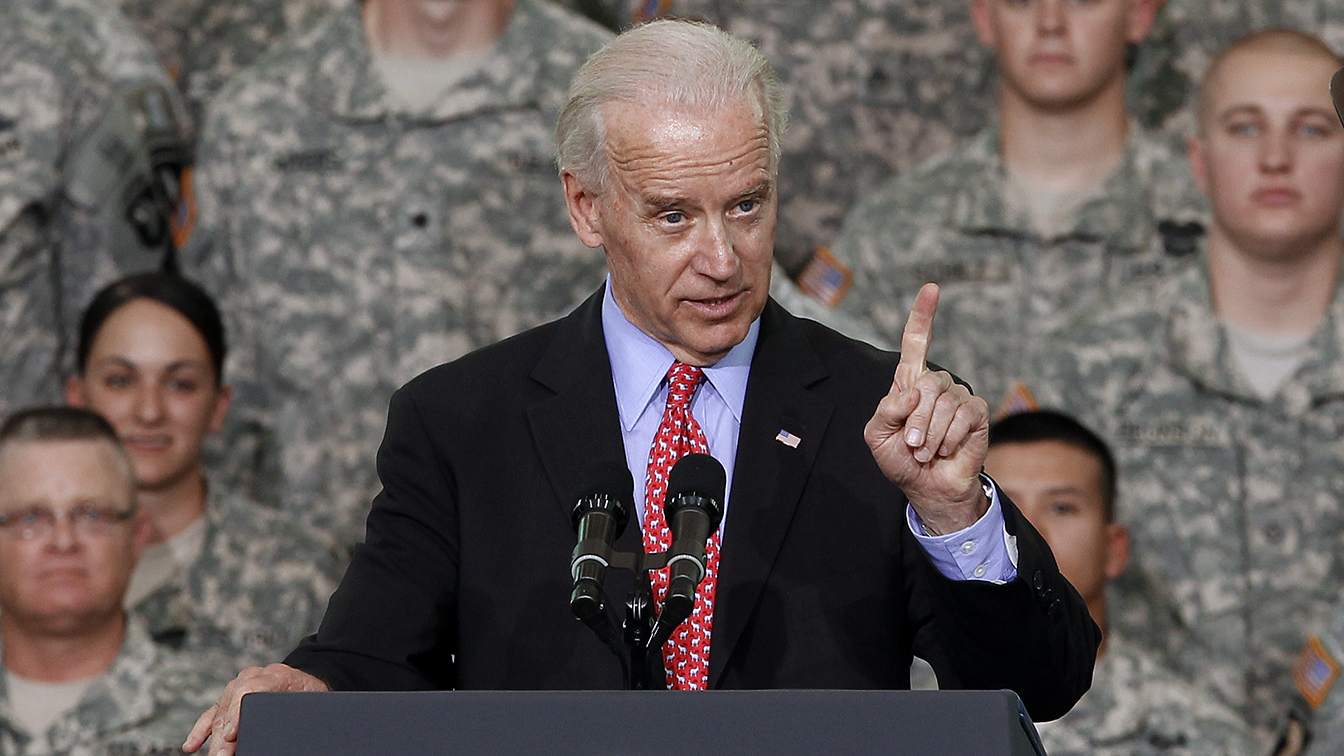

The incoming Joe Biden’s administration will have lesser options in dealing with the Afghan insurgency. It cannot choose to go offensive, despite the fact that the peace table has not registered any notable progress thus far and insurgency continues unabated.

Considering the protracted nature of insurgency and squandering of American resources, will power and popular support after almost two decades of military entanglement, the new administration will not choose an unsuccessful strategy of the outgoing Trump administration which sought to address the Afghan situation by adopting an offensive gesture soon after assuming office through measures like increasing the number of American troops and resuming drone strikes – a strategy which was later discarded and Washington was forced to open direct talks with the Taliban in view of unremitting insurgency in many pockets of the country and mounting civilian as well as troops’ casualties. Thus, the Biden administration has no alternative except throwing its complete weight behind the peace process.

Ironically, even while the peace talks are very much on between the American and Taliban representatives with a temporary pause until January 5, 2021, the supporting conditions are far from being attained. The Biden administration will have the challenge to handle the existing lacunas with dexterity and enlist support from other regional stakeholders in the process. The administration cannot hope for a hasty yet successful peace process considering the fact that the Taliban cannot be viewed as the only Afghan stakeholder in the process.

Challenge of Regional Cooperation

The American efforts at shaping the contours of the Afghan peace efforts excluding the influence of geopolitical rivals like Iran and Russia fell squarely with its geopolitical ambitions of using Afghanistan as a bridge to the resource-rich Central Asian region and becoming a predominant player in energy politics. The Trump administration heavily relied on a containment policy toward Iran and Russia by reversing the nuclear deal with Iran and imposing multiple sanctions on both Iran and Russia on various ambiguous grounds. However, the divergences of geopolitical interests drove these regional powers to maintain contacts with and embolden the Afghan Taliban to move flexibly and negotiate from a position of strength. The Biden administration may soon realize that the internal political dynamics ran in favor of the Taliban and the US could only acquire a predominant position in the Afghan scenario by turning the tide of external dynamics by bringing in the influence of Russia, Iran, China and Pakistan to the Afghan peace efforts.

Besides, while the US Afghan peace interlocutor Zalmay Kalilzad is seeking guarantees from the Taliban that the group would not allow Afghanistan to be used as a launching-pad for terror operations, this assurance from the Taliban cannot guarantee the end of insurgency by various other militant groups operating within Afghanistan. According to the statistics put out by a Pentagon report in the first half of 2019, there are as many as 20 prominent militant organizations active in Afghanistan Thus, inclusion of Afghan government and support from regional powers in the peace talks would go a long way in addressing such a gloomy scenario.

Inclusion of Afghan Government

The Biden administration will have the challenge to persuade the Taliban and enlist the inclusion of the internationally recognized Afghan government in the peace process which has been sidelined in the entire gamut of the process due to the Taliban’s insistence that it is merely an American puppet and the insurgent group’s territorial control and far-reaching influence has restricted the leeway of the external powers in nudging the Taliban from its firm position. Exclusion of the Afghan government from the peace process not only indicates cornering of the present political institutions representing the country’s fledgling democratic multi-ethnic structure, the Taliban’s intentions remain unclear as to whether the group would work with others to take whatever socio-economic and political gains have been accrued all these years ahead. Exclusion of the Afghan government from the peace process so far means that the process is gravitating toward the Taliban’s agenda which largely remains unclear.

Addressing Pakistan’s Double Game

Another challenge would be to ensure continued and perceptible support from Pakistan in the peace process. The outgoing Trump administration’s experiments with tightening of screws over Pakistan to end its double game (it was committed to fighting terrorism on the one hand by joining the War on Terror whereas it threw its weight various insurgent groups on the other) were not effective as there was a surge in the incidents of terror attacks propped up by Pakistan as a retaliatory response to US action as well as to demonstrate its influence over the insurgents in Afghanistan.

For example, after Kabul ambulance bombing death toll reached beyond hundred, the head of Afghanistan’s intelligence service, National Directorate of Security (NDS) Masoom Stanekzai stated that these actions were deadly attempts by the Pakistani backers of the insurgency to show they could not be sidelined. Neither the Obama’s policy of aiding Pakistan nor did the Trump’s strategy of withdrawing aid work to attain success in Afghanistan in the past. Laxity on fighting terrorism on its soil and failure to meet the counter-terrorism standards set by FATF led to the chances of blacklisting of Pakistan by the watchdog which it narrowly escaped this year. Pakistan would use its influence over the Afghan Taliban as a way to gain strategic depth against India and may prefer an unstable Afghanistan to see its interests served.

Challenge of Democratic Deficit

Continuing insurgency by different militant groups including the Taliban has not only targeted foreign troops and Afghan government, rights of civilians and role of civil society organizations have been indiscriminately compromised too. Mina Mangal, a prominent Afghan journalist, an advocate of women’s rights to education and work as well as a cultural adviser to the lower chamber of Afghanistan’s national parliament was assassinated indicating the macabre dimension of insurgency as well as the fragility of the peace process. Meanwhile, Afghan women’s rights activists continue to complain that they have not been represented in the peace process and fear that any American deal with the Taliban would jeopardize their freedom.

The new administration will also have the challenge to work on the structure and nature of the political system that would ensue with the Taliban joining the mainstream political process which so far remains vague. For instance, Jalaluddin Shinwari, the deputy minister of justice under the Taliban government in the late 1990s, and who still maintains contact with its leaders, maintains the viewpoint that the modern insurgency will not settle for anything less than the return of the Emirate, and has a fundamental distaste for democracy. The US as the oldest democracy with vibrant civil society groups will have the pressures to address the questions of democracy and pluralism during the peace process.