When one new ship slides down the slipway of an American shipyard, dozens of new ships are being launched from China’s shipyards on the other side of the Pacific. This stark contrast reflects a half-century-long decline in America’s shipbuilding industry, which once symbolized the nation’s industrial might.

Recently, the Trump administration proposed creating a “White House Office of Shipbuilding” to restore America’s shipbuilding glory. However, the reality is far harsher than the rhetoric suggests.

The US builds only about five new ships yearly, significantly fewer than China’s shipbuilding capacity. According to Dutch bank ING, China’s share of the global shipbuilding market grew from less than 5 percent in 1999 to over 50 percent in 2023, dwarfing the share of the US. This gap didn’t appear overnight; its roots were planted decades ago when the industry’s gears shifted. The disparity isn’t just about scale – it’s a fracture in the industrial ecosystem itself.

The chasm between American and Chinese shipbuilding is fundamentally a gap in industrial infrastructure. The forces of globalization swept away America’s steel mills, machine shops and skilled labor force, leaving behind rusting supply chains and a hollowed-out manufacturing base.

Shipbuilding, a quintessential heavy industry, requires a robust industrial foundation. When that foundation crumbles, shipbuilding inevitably follows.

Rebuilding America’s shipbuilding industry isn’t as simple as creating a new government office or throwing money at the problem. It’s more akin to replanting a rainforest in the desert. You need to restore the soil (industrial infrastructure), introduce species (supply chains) and wait for the ecosystem to regenerate (skilled workforce development).

The Trump administration’s planned investment might plant a few trees in America’s shipbuilding industrial desert, but a forest will take at least 20-30 years to grow. Of course, America’s military shipbuilding sector remains a global leader in technology. However, expanding this expertise to the broader commercial shipbuilding industry is a challenge.

This mirrors America’s difficulties in other advanced technology sectors, such as semiconductors, robotics and artificial intelligence, among others.

The real challenge for the US isn’t just maintaining its lead in high-end technologies, it’s figuring out how to apply those technologies more broadly across entire industries. At the same time, these industries must continuously innovate to push high-end technologies even further. This reality makes it impossible to discuss the revival of American shipbuilding without acknowledging China’s role.

For Washington, the solution requires more than new industrial policies – it demands a shift in perspective. Viewing China solely as a rival is like trying to compete in the digital age with a steam engine mind-set.

Meanwhile, China’s shipbuilders and competitors have deepened their cooperation recently.

A Norwegian company reduces shipbuilding costs by buying an LNG and fuel dual-powered car carrier. Dalian Shipbuilding and NYK’s NBP will jointly build a 33,000-ton deck carrier, marking China’s entry into the high-end Japanese shipbuilding market. These examples show that cooperation and competition can coexist.

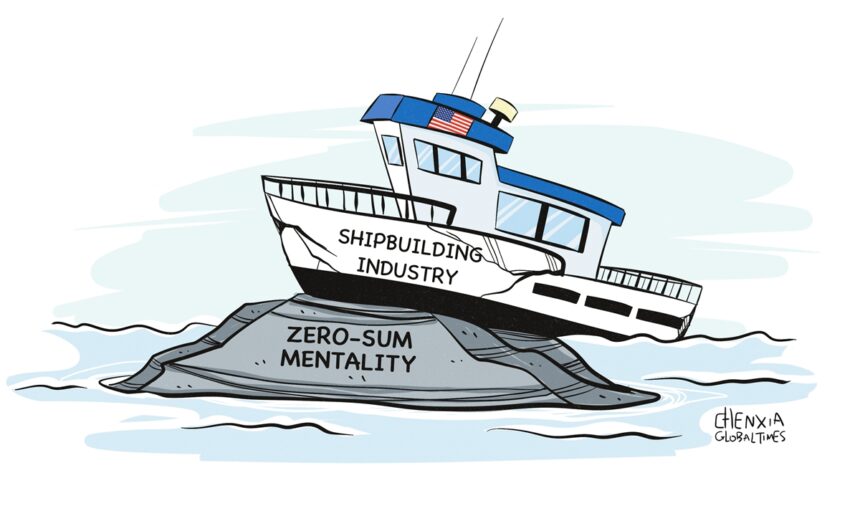

But cooperation isn’t easy. Washington needs to rethink the relationship between collaboration and competition, avoiding the trap of reducing China-US relations to a zero-sum game.

Labeling every proposal for cooperation as a “security risk” only creates a climate of paranoia. This mind-set is akin to locking your factory in an iron cage – it might seem like you’re keeping out a potential threat, but in reality, you’re stifling your growth.

Faced with the rise of China’s manufacturing sector, exemplified by its dominance in shipbuilding, America risks boxing itself into a corner.

After all, the Pacific Ocean is vast enough for ships from different nations to sail forward together.