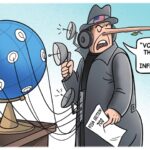

Western media have appeared to function under a consistent principle – whenever international affairs are at play, they are framed as a stage for major power rivalry. Unsurprisingly, the just-concluded ASEAN Summit was once again interpreted through the lens of US-China competition. This time, however, what was revealed was not US’ diplomatic advantage, but rather its increasingly visible diplomatic predicament.

On Friday, Bloomberg commented that the summit in Laos from Wednesday to Friday gave the US government an opportunity to showcase the relationships it has cultivated across Asia since renewing a diplomatic push three years ago. Instead, China appeared to have seized the moment.

The Bloomberg article mentioned even as the US and its allies criticized Beijing for its actions in the East and South China Seas, China reached a series of deals with regional countries. Bloomberg listed that China and ASEAN had announced plans to upgrade and broaden an existing trade deal; Beijing pitched accelerating rail projects with Thailand and Cambodia, and agreed to lift restrictions on lobster imports from Australia by year end. In contrast, there were few major new policy initiatives from the US, beyond a joint statement on promoting safe and secure policies around artificial intelligence.

Between the lines, there seems to be an underlying question from Bloomberg: After the US had made that much effort in emphasizing the South China Sea affairs during the summit, why did so many countries still cooperate extensively with China?

This tone highlights the dilemma the US confronts in its strategy regarding the ASEAN region.

China and US’ policies toward ASEAN are clearly differing. China seeks to promote cooperation and mutual interests constructively, while the US adopts a passive, fear-based destructive strategy, aiming not to foster development in the region, but rather to thwart any progress that it does not favor, Shen Yi, a Fudan University professor, told the Global Times.

Shen added that China views ASEAN as a neighbor, with which China seeks to promote friendly relations and foster common prosperity. In contrast, the US strategy toward ASEAN is designed to encourage member countries to hold back China’s growth and create obstacles for its development. Before ASEAN possibly follows US’ lead, it must address a fundamental question: What are the benefits of doing so?

Take the Philippines. Washington has been encouraging Manilla to provoke frictions with Beijing, but when tensions escalate, it offers only symbolic reassurances. When the Philippines faced challenges in economic development or went through crises like flooding, how has the US contributed to improving the livelihoods of Filipinos? Coverage on this is notably scarce.

The US seems to have a misconception that tensions in the South China Sea will automatically lead Southeast Asia to align with the West, which is clearly at odds with reality.

Setting aside the fact that this round of tensions in the South China Sea is inherently linked to the US hidden hand at work behind the scenes. Aside from the Philippines instigating tensions, no other ASEAN member countries have followed suit. Even when Philippine President Marcos personally attempted to rally Vietnam and Malaysia to form a united front in the waters, his efforts ended in failure.

Leaders from countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia have proactively visited China to reaffirm their traditional friendships. This clearly demonstrates that ASEAN member countries do not want to see chaos and conflict in the South China Sea and they are unwilling to relinquish opportunities for cooperation with China. ASEAN members are keenly aware of the external forces seeking to disrupt regional peace and development.

Development and prosperity are the consistent pursuits of ASEAN. For example, in recent years, the themes of the ASEAN Summits have been “ASEAN: Enhancing Connectivity and Resilience,” “ASEAN Matters: Epicentrum of Growth,” and “We Care, We Prepare, We Prosper.” This clearly indicates that they do not want to become a stage for geopolitical confrontations. However, the constant US hype over “China threat” across a number of platforms, attempting to shift the focus of ASEAN discussions, is not what ASEAN wishes to see.

US media often try to underline Washington’s efforts to strengthen ties with ASEAN. However, if these efforts were truly effective, why do projects under the Belt and Road Initiative still hold significant appeal in ASEAN? This is particularly noteworthy given the US tactics of constantly driving a wedge between China and its neighboring countries. Perhaps the problem lies in the direction and the way of US investments.

The US diplomatic predicament stems from its lack of sincerity. Its various cooperative mechanisms with ASEAN and its member states often harbor ulterior motives, overtly or covertly targeting China. Not to mention that under its “Indo-Pacific Strategy,” the US has established a series of mini-lateral mechanisms, aiming to make its own network of regional partners the dominant one, which poses a significant challenge to ASEAN centrality.

In this context, ASEAN’s important neighbor China is genuinely advancing friendly relations and common development through tangible projects. What should ASEAN do? The ASEAN countries are not naive. They know what is beneficial to them.