According to recent findings of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the total global defense expenditures in 2023 reached a staggering $2.44 trillion. SIPRI’s annual Trends in World Military Expenditure review concludes that this was the highest yearly increase in defense spending since 2009 and that never before had mankind spent so much money on military preparations. Nation-states spend, or waste, 2.3 percent of their collective GDP to protect themselves from each other. Incidentally, this dubious achievement is well above the stated NATO goal to oblige all of its members to allocate no less than 2 percent of their GDP to defense.

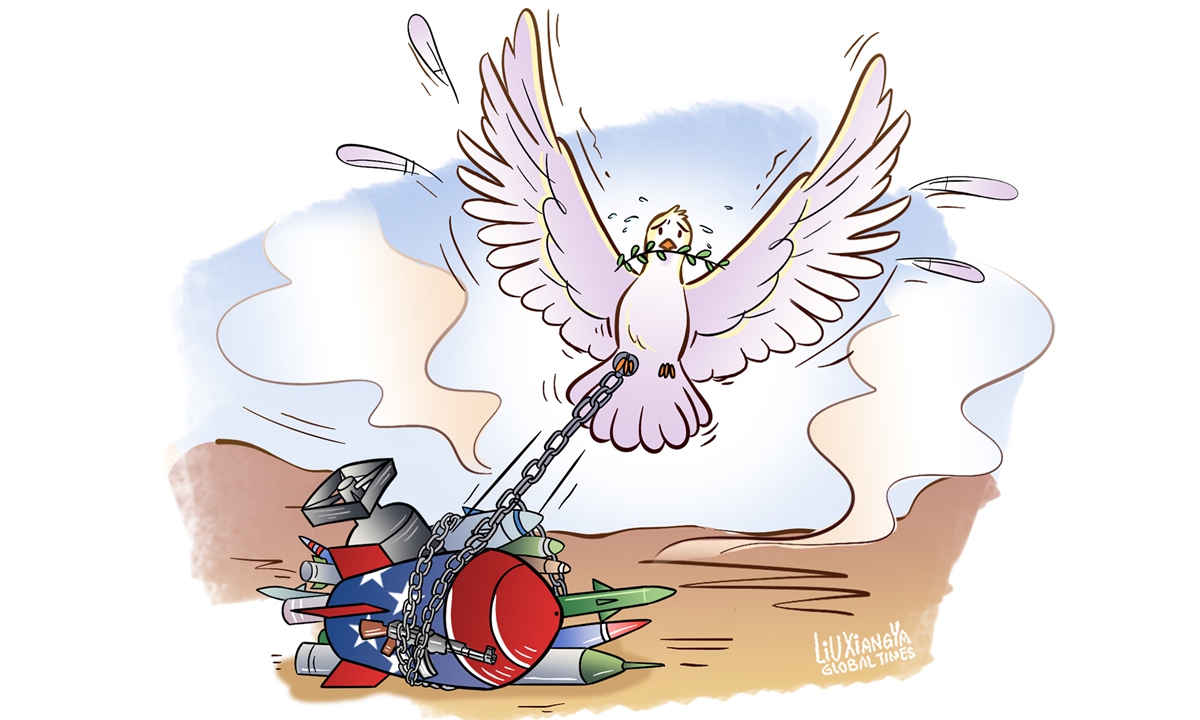

No doubt, national leaders find many compelling reasons for their decisions to raise the stakes in global military competition. As many times before, they are actively engaged in an endless blame game with a clear intention to impose all the responsibility for the arms race on their geopolitical opponents. However, cold hard data leaves little room for ambiguities – the US remains an indisputable global leader with the Pentagon’s budget of $916 billion. NATO spends $1.34 trillion or 55 percent of the global expenditure. If you add to these statistics the rapidly growing defense budgets of such counties as Japan, South Korea and Australia, the undeniable responsibility of the West in the global arms race will look even more explicit.

The same clear trend can be traced in the global arms trade. According to SIPRI, over last five years the US export of arms has increased by 17 percent and the US share of the global market has jumped from 34 to 42 percent. The statistic on NATO is also indicative – the Alliance share in providing arms to foreign countries in 2019-23 has grown from 62 to 72 percent. A particularly steep growth of 47 percent in five years was demonstrated by France. Most of the forecasts suggest that the US and its allies will continue to enhance their positions in providing weapons to the rest of the world.

Given all these trends, it comes as no surprise to hear that the US leadership has often been skeptical about arms control. In 2002, under president George W. Bush, the US withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty that for 30 years served as a foundation for strategic stability between Moscow and Washington. In 2019, the Donald Trump administration terminated the US participation in the INF Treaty, which since 1987 banned Moscow and Washington from producing, testing and deploying ground-based missile systems with an effective range of between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. The US never ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty.

Despite many claims that the US has always strongly opposed nuclear proliferation, the existing American nonproliferation track record is at best dubious. For instance, the decision of the Joe Biden administration to supply Australia with three US Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines by the early 2030s raises concerns about the future of nonproliferation.

In January 1961, president Dwight Eisenhower warned Americans about the increasing power of the military-industrial complex. The interplay of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry contained new risks not only for the US foreign and defense policies, but also for the American society at large. American citizens should therefore be vigilant in monitoring the military-industrial complex. Unfortunately, the last few decades fully confirmed the fears of president Eisenhower, but have not yet demonstrated the ability of the US political system to identify and to deploy adequate means to contain the power and the greed of the omnipotent defense contractors.

The current geopolitical situation is not conducive to any manifestations of self-constraint, not to mention any far-reaching disarmament initiatives. Strategic arms control between Russia and the US is completely and arguably permanently stalled, and conventional arms control in Europe is no better. To talk about any meaningful arms control in the Middle East or in Northeast Asia today would be considered ridiculous if not preposterous.

The SIPRI review appropriately links the ongoing defense boom to the conflicts in places like Ukraine and Palestine, as well as growing tensions in many other corners of the world. The chances for 2024 to become the decisive turning point from wars and crises to peace and reconciliation are very low. Even if the ongoing conflicts were somehow miraculously stopped tomorrow, the global arms race would still continue. Modern military procurement programs have a lot of internal inertia. Strategic ballistic missiles, strike submarines and aircraft carriers that are being designed today are likely to be fully deployed only in 15 to 20 years from now and they are going to define the global strategic landscape for most of the second half of the 21st century.

The problem is not only about resources that are taken away from what the real and urgent needs of the humankind are. A continuous arms race should be regarded not only as a function of mutual mistrust, tensions and military conflicts, but also as a prime source of all of the above. In a world stuffed with ready to use lethal systems, the risks on an accidental and inadvertent war are getting higher. The creeping militarization of world politics turns international relations into a zero-sum game, in which the goal is not to resolve a difficult problem, but rather to defeat the opponent.

As the Cold War experience demonstrates, only strong public pressure could force reluctant leaders of the global arms race to reconsider their militant positions. It was noted a long time ago that recovery from addiction is not for people who need it, but for people who want it. The same can be said about a recovery from the global arms race.

The author is academic director of the Russian International Affairs Council. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn