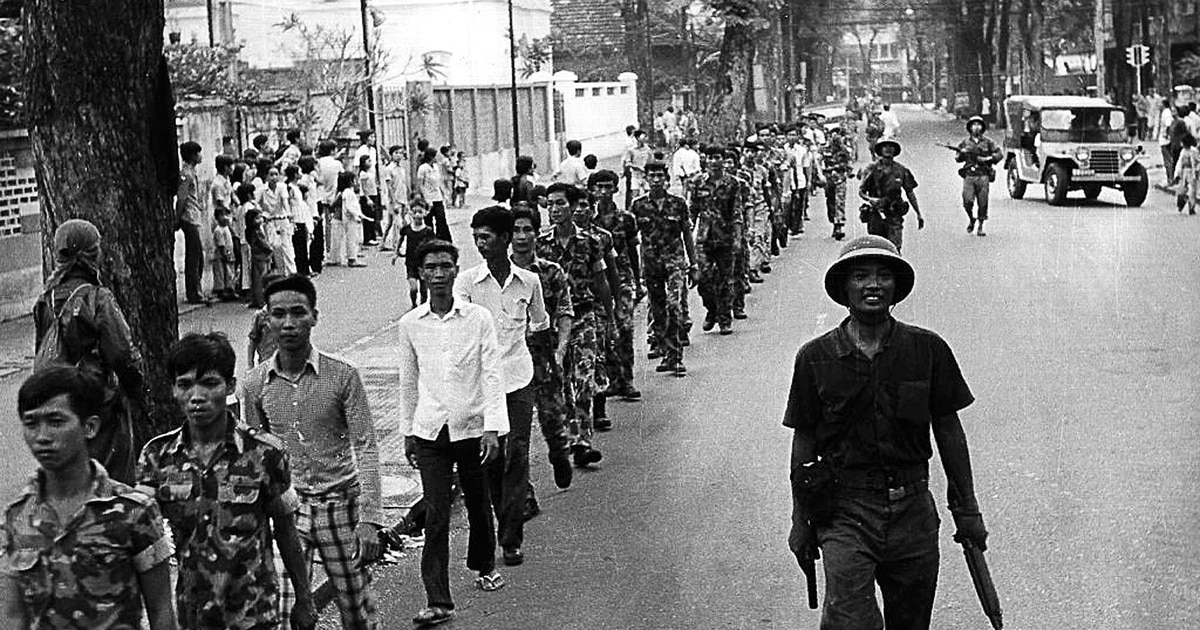

An April 30, 1975, photo shows a line of captured U.S.-backed South Vietnamese Army soldiers, escorted by Vietnamese communist soldiers, as they walk on a Saigon street after the city fell into the hands of the communist troops on the same day, marking the end of the Vietnam War. (AFP via Getty Images)

The parallel between the Vietnam War and Afghan War is troubling. In both cases, the U.S. became involved in a foreign war without having a clear picture of what our ultimate objective was. We largely took over the direction of each war from a corrupt host government. Many citizens of our host country placed reliance on the U.S. to provide for their safety, come what may. The war became unwinnable because of a series of unfortunate decisions. Losing interest in the endeavor, we shaped settlement terms the host government was required to accept, intimating we would be there to help if worse came to worst. Here, the similarity ends, for now.

In the case of Vietnam, even though we knew weeks beforehand that the fall of South Vietnam was imminent, we made no concerted effort to extract the Vietnamese who had steadfastly supported the U.S. When their government fell, many thousands who had helped, trusted and relied upon us were murdered or incarcerated to the great dishonor of our nation. Hundreds of thousands of refugees fled the south and, although we gave many of them sanctuary, our help was slow in coming. The final chapter in Afghanistan has yet to be written, but it must not end up with a betrayal of our friends.

During the long and tortured course of America’s war in Afghanistan, many Afghans stepped forward at their great peril to serve and help protect our military personnel. As we withdraw from Afghanistan, the Taliban have stepped up their violent attacks and the danger to our friends has dramatically increased. We are morally obligated to provide them sanctuary within our borders.

There are two special immigrant visa (SIV) programs in place to bring our Afghan friends to the U.S., but they are mired in red tape — it takes up to three years to process an application. There is a backlog of nearly 19,000 SIV applicants, with about 50,000 family members. They are waiting in line, living in fear of death. There are not enough slots to take care of the backlog. The vetting process is understaffed, underfunded and overly burdensome.

In this crisis situation, there are two feasible alternatives — either review existing documentation in the files and grant visas to those who U.S. personnel have credibly vouched for in the files, or extract the SIVs and families from Afghanistan and complete any necessary vetting in a safe location. We processed South Vietnamese refugees at U.S. military bases in the late 1980s.

We need, also, to consider the plight of Afghans who don’t qualify for SIV status. A Taliban take-over, which appears increasingly likely, will create a flood of refugees, fleeing for their very lives. Being partially responsible for their plight, we are honor bound to provide sanctuary for many of them, just as we eventually did for those fleeing Vietnam. We should plan to evacuate Afghans who will be targets of Taliban reprisal — uncorrupted government and military officials, women’s rights advocates, educators, democracy advocates and the like.

Like many troops who served in America’s wars, this issue is very personal for me. I lived and worked with South Vietnamese soldiers in 1968-1969. I trusted them with my life, while they relied on the U.S. government as a friend and ally. Most of my Vietnamese friends were Catholics who moved from North Vietnam to Tay Ninh Province in South Vietnam in 1954 to escape persecution. They were fiercely anti-communist and pro-American. It broke my heart when the communists took over in April 1975, knowing that my friends would be killed or imprisoned, as were many thousands of their countrymen. We had a moral obligation to extract as many as possible but, instead, we abandoned them to a horrific fate. We simply cannot allow that kind of tragedy to happen again with the Afghans. I pray that this great nation does not again turn its back on beleaguered people who placed their trust in us.

Jim Jones is a Vietnam combat veteran who served as Idaho Attorney General for eight years and as an Idaho Supreme Court Justice for 12 years (2005-2017). He has written about his Vietnam experience in “Vietnam…Can’t get you out of my mind.”